Here we go, then; like a murderous doll coming back

to life in a warm car, like Jon Pertwee lassoing a psychic, psychotic machine

with copper wire, I am taking charge of this

blog. I am channelling all the power of the Nuton Energy complex back into the

space vampire that is my life. Eko! Eko! The

Dandy!

Yes, I skipped a couple of stories. Well, a whole

season. And what a season! Let me bring you up to speed...

I must say, Dr Who sometimes seems his own

worst enemy. Exiled to live life one day after another on the same planet, does

he exorcise any of his wanderlust by traversing the globe, exploring the places

he hasn't visited: Berlin , San

Francisco , Tokyo

A couple of incarnations ago, of course, he was

hardly Prince Charming. As an impetuous young grandfather, he could hardly stop

himself being tetchy in order to be patronising. What's the difference here? Perhaps

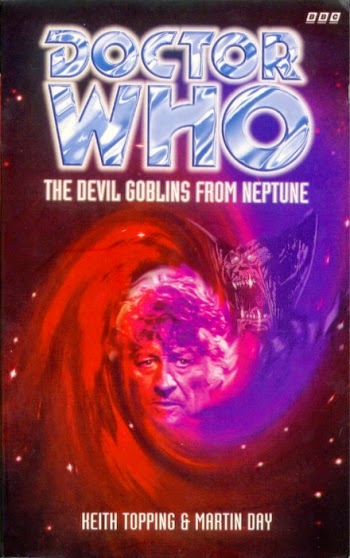

it's that Pertwee (51, here) seems so much the younger man, for all that his

curling white hair is his own, unlike Hartnell's (55 in his first story). His

mind is pin sharp, and so is his tongue - and everyone ends up on the wrong end

of it, eventually.

Of course, he's going through a difficult period.

As if exile to the Home Counties wasn't bad enough, at the start of this season

his side-kick Liz Shaw has just quit his company after what sounds like a row:

later that day he finds a criminal megalomaniac has moved into his territory.

The Master's like the neighbour from hell, except he's really just passing

through - his vehicle isn't metaphorically sitting on a pile of bricks in the

garage. Soon, everybody's asking 'Who is this Master guy?' All the

Doctor gets is grief from civil servants.

Of course, the Doctor isn't so badly off. Liz may

have gone off to handle her own test tubes in Cambridge

It's light on its feet, effortlessly sketching in

the backgrounds of characters who essentially appear on telly in order to be

terrorised by Roger Delgado and his blank-faced henchmen, including Jo Grant

herself: he spins a real story out of the TV version’s cavalcade of set-pieces

(in retrospect, the TV version is just four episodes of cliffhangers) (but what

cliffhangers!). On Jo's first day, she's already heard of the Doctor - you

picture him as something of a public figure - and Dicks draws a real narrative

out of her First Day from Hell.

I have to admit, though, I don't get a strong sense

of Jo after her first five stories. Everything feels quite new to her - in Colony in Space, she doesn't even believe

the Tardis can fly through time and space (so goodness knows what she thought

was going on in The Claws of Axos,

when much is made of the Doctor's vanishment in a cosmic huff). The Dæmons gives her some fun dialogue,

baiting the Doctor - she even saves the day - but in many ways she still feels a

supporting artist: someone to ask questions and lug trees out of the way of

Bessie. The Brigadier, by comparison, is barely involved in the story proper

but gets constant character notes and moments of triumph.

Katy Manning is, of course, fantastic - her finest

hour being, probably, The Mind of Evil,

when her compassion for Barnham is a nicely played counterpoint to the vicious

machismo exploding at every hand. She also has to take care of the Doctor after

he is nearly destroyed by the nightmares induced by the Keller Machine. This

story features one of the only real character moments for the pair of them -

until The Dæmons, which is in quite

another register - with the Doctor reminiscing about his travels to his young

companion. If she thinks he's Baron Munchausen at this point, she's more than

prepared to humour him. It's the kind of scene you'd get constantly now - the

fact that it's so rare here only makes it more cherishable.

She also gets quite a lot to do in Colony in Space, although much of it

involves being held hostage and rescued. I love the moment when she and a

colonist are chained to a bomb in a cave. 'What do we do now?' he asks her. She

shrugs, almost blithely: 'Escape?' It's a rare moment of strength for Jo, and

Manning's performance is entirely adorable. Her performance - innocent,

frequently outspoken - is just crying out to be matched by Roger Delagado's.

Delgado is perfect in every story. If it was hard

to ever imagine Patrick Troughton as a Lord of any kind, the Master oozes the confidence

and glamour of the aristocracy. The universe is a giant costume party for the

Master, and whilst he might start this series masquerading as an electrical

engineer, it's not long before he's a High Court Judge In Space, a vicar and

the leader of a black magic coven. It's a shame we always see him at work - it

would be fabulous to observe the Master on holiday.

And it doesn't hurt at all that he's in every

story. It would be thrilling if there was causality between his multiple

appearances, but there's not, and his repeated appearances are gloriously camp,

even comic, as in Colony in Space. Yet

there are cracking scenes between the pair of them throughout the series. The

Master sincerely wants to share the power of the Doomsday weapon with the

Doctor, and doesn't raise Azal casually: he wants to rule. One big scene in

Peter Capaldi's Death in Paradise

reconnects with that idea - the Master doesn't just see the Doctor as weak, he

thinks him petty and small-minded.

One final note - I only knew two of these stories.

But in story two, I knew where I was. There's an aesthetic to the Pertwee era

that is quite addictive, all on its own: lurid visuals, big performances, music

and sound effects that make your TV sound like it's going to blow up. There is

some fabulous writing here too, but I think this is what I particularly adore

about this era. It's cosy. It's creepy. But it's also out of control - like so

many machines in these five stories, it constantly sounds like it's about to overload

and self destruct.

And here we are on the threshold of Season 9, and

the return - four and a half years since their 'Final End' - of the Doctor's real arch-enemies...

Oh, and I didn't mention Miss Hawthorne...!

.jpg)

+6.jpg)